by Maggie Dugan

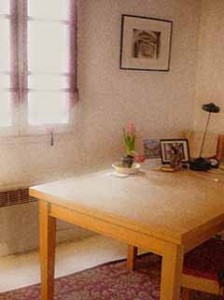

I was seven months pregnant when I decided that it was time to start writing, really writing, the sit-in-the-chair-every-day kind of writing. Within a month I rented a tiny studio across the street from my apartment and furnished it with only the necessary items: a writing table and chair, a lamp, a computer. There was no telephone and no connection for Internet access.

I’d been a writer for as long as I can remember, it’s just that I’d been writing for everyone else. I was a journalist, and I headed up a small radio network. When I moved to Europe, it was with the intention to write. But within two-years I jumped back in the grind, working just as hard, churning out lengthy documents once again, for somebody else. I even ended up in Paris where it’s in vogue to sit in cafés and write, but I wasn’t really writing, not the kind of writing I wanted to do.

I didn’t want to let my child become an excuse not to write, and I didn’t want to resent her because I’d stopped chasing a dream. I knew having a place to go to write was the only way;  if I didn’t have a room of my own, nothing would change. Two years later, a second daughter followed and there were more demands on me than before. But I kept crossing the street, climbing the narrow stairway to my little atelier and facing down my computer. Sometimes I’d sneak over at night after the girls had gone to sleep. With only the dim light of a table lamp and the glow of my computer screen, I could see my reflection in the dark window. I’d nod at myself, certain that whether my words were published or not, what my daughters would witness was just as important: seeing their mom making time to do what she loved, simply because she loved it.

if I didn’t have a room of my own, nothing would change. Two years later, a second daughter followed and there were more demands on me than before. But I kept crossing the street, climbing the narrow stairway to my little atelier and facing down my computer. Sometimes I’d sneak over at night after the girls had gone to sleep. With only the dim light of a table lamp and the glow of my computer screen, I could see my reflection in the dark window. I’d nod at myself, certain that whether my words were published or not, what my daughters would witness was just as important: seeing their mom making time to do what she loved, simply because she loved it.

Of course, in order to model this for them, I had to really learn it.

I had to learn how to put myself in the chair and just write, no matter what. I had to learn to pour myself on the page and live with an awkward and imperfect first draft. I had to learn – I’m still learning – to silence the judge that critiques my work too quickly and keeps me from putting it out for the world to read. The hardest part to learn is the patience; giving the process time, and to just to keep doing it anyway.

It sounds romantic, the life of a writer in Paris. Now that I’ve been doing it, I know what a grind it can be. Still, I keep making the trek across the street, putting in my time in my little studio. Sometimes it hurts to sit there. Sometimes it feels so natural that I can’t stop smiling.

I want to tell you something about my mother. She was a model of professional and domestic organization. She made a list of every product she would ever consider buying at the local supermarket, in the order of how they were placed the aisles of the store. She typed it up, made a hundred copies and bound them in a large note-pad that she kept on the kitchen counter. As we ran out of supplies, she checked each item we needed. On Thursdays, she’d tear off the top page and take it with her to buy the groceries. Nobody got in and out of that store faster than my mother.

She had a list for everything and it seemed her satisfaction was measured by how many boxes get checked off. Even opening the Christmas presents was something we had to “get out of the way.” After the first day of school she’d ask how many children were in my class, but she never asked what it felt like to be assigned to a different class than my best friend of the last three years.

As I grew into a woman, I wanted to share with my mother the deeper parts of my life, but I found she couldn’t talk about her emotions and she didn’t really want to hear about mine. I asked her what was it like the night my father died; she told me about getting the telephone to work with her hearing aid, and how the sheriff drove her to the hospital behind the ambulance. The pain and anguish of watching her husband die – and the loneliness of her life since – was left out of that recollection.

This morning, standing at the kitchen counter eyeing the clock and trying to get out the door and across the street to my own room and my own words, I’m caught in the web of things to do. Something is wrong with the vent for the kitchen fan, it’s raining and water is dripping in on the stovetop. I stand on a chair trying to wipe the excess water from inside  the fan unit, thinking about how to find the phone number for a roof-top chimney repairman, remembering that I also need to call and make a doctor’s appointment for the kid’s vaccinations. I have to stop by the conservatory to organize the music class schedule and file the insurance papers for the musical instrument we rent from them. The other daughter needs a gift for an upcoming birthday party, and there’s a note in her cahier that she needs a specifically-sized binder notebook for school, by tomorrow. The girls’ ID cards must be procured at the prefecture, an ill-timed administrative errand that disrupts time I’d set aside to work, but urgent because of an upcoming trip. There are a dozen tiny things like this on the list, none of them on their own particularly time consuming, but their accumulation and interruptive quality stuns me. That long chunk of hours I’d set aside to write squeezes in on me like the narrowing walls of a horror movie; I finally get to my studio and just as I fall into the groove of concentration, it’s time to go wait outside the school and bring the girls home.

the fan unit, thinking about how to find the phone number for a roof-top chimney repairman, remembering that I also need to call and make a doctor’s appointment for the kid’s vaccinations. I have to stop by the conservatory to organize the music class schedule and file the insurance papers for the musical instrument we rent from them. The other daughter needs a gift for an upcoming birthday party, and there’s a note in her cahier that she needs a specifically-sized binder notebook for school, by tomorrow. The girls’ ID cards must be procured at the prefecture, an ill-timed administrative errand that disrupts time I’d set aside to work, but urgent because of an upcoming trip. There are a dozen tiny things like this on the list, none of them on their own particularly time consuming, but their accumulation and interruptive quality stuns me. That long chunk of hours I’d set aside to write squeezes in on me like the narrowing walls of a horror movie; I finally get to my studio and just as I fall into the groove of concentration, it’s time to go wait outside the school and bring the girls home.

I understand, now, why my mother deflected her feelings with logistics and figures and the items on her list. She couldn’t afford the time it takes to feel. That was how she coped, how she kept the engine of our household going. I’m acutely aware of how easily I could avoid the feeling part of my life. There’s always so much to do.

That’s why I write. Writing means, to me, feeling my life. Writing forces me to dig deeper than the first layer of disclaimers and excuses, to explore the murky, feeling world beneath. The first words on the page start out as something cerebral, they evolve into a portal for raw and real emotions. Writing takes me beyond being a thinking woman, or a doing woman. It demands that I be a feeling woman, too.

Since I took my studio and started taking myself seriously as a writer, I’ve learned that being engaged in what I’m writing is one of its greatest gifts. I’ve learned how essential it is to feel the tiny pointed details of every day and connect them in the map of how I live my life. Writing is what spans the territory I inhabit, the bridge between how I wanted to know my mother and how I hope to know my daughters. The pivot point is in that chair, alone in the peace of my writing studio. It’s there that I feel the next sentence, the next paragraph – one by one – each day writing a page of a life that is fully lived, feelings and all.